Being a Teenager During September 11th, 2001: Irony, Poetry, and History Making

I had known all along that I didn’t want to be a journalist. I had known it early in high school, after the school newspaper’s Levendis editor assigned me my first Arts & Entertainment article on Pokèmon. I discovered then that I didn’t like talking to people who I didn’t know.

But there I was, early in my senior year of high school, 8th period, alongside my fellow Arts & Entertainment editors Mark and Chris. It was September 11th, 2001, and earlier that day, during 2nd period, our entire school had listened over the loudspeakers to the news from New York City, live, including hearing the reaction of the broadcasters as the second tower fell. I had been surprised to see my peers pulling cell phones from their bags to call to see if their parents who worked in the area were okay—kids my age had cell phones? Parents from Cherry Hill, NJ travelled all the way to New York City for work?

In the middle of the day, we watched the repeated footage of the towers aflame, the planes crashing into them, during Phys. Ed. as the news stations on the television in the gymnasium played it again and again and again. In some of my classes, my teachers ran improvised lessons—what can we learn from this? How do you feel about this? In others, we sat at our desks quietly. The name Osama Bin Laden traveled the lips of my fellow students, many who were Jewish with an interest in the Middle East that I lacked. I’d never heard of him.

My math teacher, 7th period, Ms. Hu, if I remember correctly, ran our math class as though nothing had happened. A fellow student kept raising his hand, saying, “Can we talk about what happened earlier?”

She ignored him.

“I really can’t focus on math today.” His hand waved incessantly in the air.

“Ms. Hu. Can we talk about New York?”

She paused. His eyes lit up. “We are learning our pre-calc today like any other. Open your book. Get out your homework.” She went around the room and checked our homework. I diligently took notes that I wouldn’t understand now, probably didn’t understand then. And not because of what became known as “9/11” but because I was horrible at pre-calc.

But 8th period, my fellow Eastside editors and I shared my most common emotion that day: confusion. I had written in my journal over and over throughout the day that I wanted to go home and see my family—but I also had taken notes as to what was going on around me. Something between shock, sadness and… dare we admit, excitement, filled the air in that last classroom. This was a tragedy, yes, and terribly sad—but it was history in the making, and here we were. Were we allowed to feel this undercurrent of excitement that ran hot, below the grief and the fear? It was confusing, to say the least.

That night, the PATCO trains didn’t run. Where I lived in Ashland, their back and forth every fifteen minutes or so were key to the noises that sung me to sleep. I defined the mood, in a note to my best friend Jordan, as “that snowstorm silence”. The only other time the trains didn’t run that I could recall was during blinding white blizzards. I didn’t talk to anyone on the phone that night. I sang “God Bless America” along with the House and Senate when they broke out into it on the television. I watched the same images we’d watched in the gymnasium, but this time sitting next to my mom and brother, relieved to be surrounded by my family.

The next day Jordan and I exchanged notes on yellow lined pieces of paper, his just as spooky and well written as mine. This is what we did. We recorded history in the slanted light. But as an Eastside editor, I still had a duty to my fellow students at Cherry Hill High School East.

That next day our journalism teacher, Mr. Gagliardi, led us into probably the best discussion we would have about the tragedy: As editors, what should we do? Our fearless four-part editorial board agreed that we needed to do something. We talked it out. This was history. This was the most tragic thing that had happened on a national level in our lifetime. We ran the school newspaper. It was our responsibility to publish something, to get something out there that physically and emotionally captured this moment in time, and quickly. One of the editors in chief (who would go on to marry, no kidding, one of the others) said that she had an idea for the editorial. She went home to write it, we discussed it the next day, and soon then we had it printed.

We published a one page editorial, “Where Do We Go From Here?”, a couple of days after the tragedy, our Eastside banner, one article, one photograph. It was a beautifully sad piece that mourned the victims and also briefly mentioned an occasion where a student at our school of Arab decent was pushed by another student. One line. The day it came out, the editors were buzzing throughout the day about gossip that our principal was angry and threatening to pull our budget— because of that line. That day, we sat in 8th period for a meeting with the principal. All of us: Gags and the whole masthead. We were to tell him who did the pushing and who was pushed, or he was going to shut us down. It was serious. We had done something serious enough to get attention, direct, in-person attention, from our school’s principal.

I had never been suspended. I had barely missed a day of class. I never even got a single detention throughout my entire public school career. And here was the principal, in person, days after our nation’s greatest tragedy, and we were in trouble. This was scary—and exciting.

I remember little about the resolution of that incident, only that we were allowed to continue to print newspapers. Only that we did not want to tell him who the people in the incident were, yet we also stood firm on the validity and the confidentiality of the report of the incident.

The first full-length issue of Eastside was also, of course, in part a tribute to 9/11. The front page was a beautifully melancholy photograph of an American flag balloon in the sand. Chris, Mark and I had fun designing the Levendis section. The two of them were especially good with witty headlines, and many times, we chose what articles we assigned based on how amusing a headline they could produce was. We had a mournful article titled, “…And the Band Played On”. We wrote about the movies that had been delayed in their release, as well as about how MTV played only music for the day of and days after. That latter we titled, maybe too cleverly, “WTC Puts the M Back in MTV”. Was it too soon for a rhyme like that? Well, we didn’t care.

The centerfold of that issue was dedicated to promoting the idea that displayed a quote from an article by one of our editors in chief that read, “America must uphold its tradition of sarcastic humor that helps keep the country honest.” The following year, Eastside, an award-winning newspaper to this day, implemented a humor section as a regular feature. Gags says, about that next issue, “the message on the double-truck was that, two months later, we needed to be able to laugh again. So the double-truck had four (maybe five) humor columns unrelated to 9/11.” We knew what we were doing, and we meant every word of it.

While late night hosts and comedians were at a loss for words, proclaiming irony dead, as teenagers, we knew that it wasn’t or at least that we couldn’t allow it to be. What would have happened if irony died with the tragedy of the Civil War? There would have been no Mark Twain, no Huck Finn. We knew that humor operated in part as a way to cope with tragedy. Had America forgotten this in its burst of patriotism? Decades prior, when cultural critic Theodor Adorno wrote, “How can one write poetry after Auschwitz?” Mark Strand, American poet, famously retorted, “And how can one eat lunch?” (a conversation taken from the essay “Uncommon Visage”, Joseph Brodsky.) We understood Strand better than Adorno. Life would go on. Things could still be funny, still had to be funny.

My brother and his friends were a few years younger than my fellow editors and I were, but they also found a way also to share in the history making during this tragedy, though not through comedy. One of them had made a sign that said “Honk 4 America”, and others soon joined, making similar signs. They stood at an Ashland intersection, encouraging rampant honking from passerby. At some point, someone pulled over and gave them $20.00, and my brother and his friends decided to use the intersection they’d taken over to raise money for the Red Cross. (The money eventually went, instead, to a New York Fire Department, in memory of a fallen firefighter, Michael Kiefer, who was 25. I still have one of the memorial buttons that came with the thank you letter my brother received.) They made more signs and all stood around that intersection the weekend after 9/11. Every honk they received elicited cheers. This went on for a few hours every day for a few days— until the world started pulling itself back together again, until it got boring.

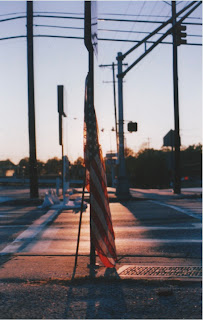

I came by their intersection with my SLR loaded with color film and took pictures of them, as well as of American flags that the gas station, owned by people of Arab descent, had leaning against a street sign and also displayed between their pumps. (See the first image above in this post for the flagpole shot). I finished that roll of film on a photography field trip our photo class took after that weekend. I took pictures mostly of a flag, waving in the beach wind. The cover that would grace Eastside’s first full-length cover was taken by a peer on the same photo trip.

During my senior year, I also ran the school’s literary magazine, Demogorgon, where, at the end of the school year, my work and others’ was featured in a beautiful, bound copy with a color cover. After we first began to bomb Afganistan, I wrote a vignette about driving up the Jersey turnpike, listening to WTRI Philly and its news briefs about how we were seemingly indiscriminately attacking the Middle East. As a friend of mine put it, humorously, when adults weren’t even allowing themselves to laugh at all, “They terrored that whole city, and now we’re terroring the terrorists. That doesn’t work.”

The piece I wrote that was published in Demogorgon is still my Nana’s favorite work by me. She always refers to it as “that piece you wrote about the bombs, about blowing up the other side of the world,” referring to a repeated line in the vignette. “That one’s my favorite. I still show it to my friends. I understand it,” she says proudly. She claims also that she relates to it emotionally, she can feel what I mean. I’m glad that she can relate to it, too. It felt good, as a blossoming teenage writer, to write something that adults connected with, were moved by.

***

I went to the Boog City Arts & Music Festival this past summer. Boog City is a New York-based publication that celebrated its 20th anniversary during this festival. The literary arts journal I now run, Gigantic Sequins, had a table at the small press fair there, and Boog had invited me to read poetry as well. The Sunday that I read, they held a panel discussion between three writers on “The Death of Irony; The Triviality of Poetry in the Face of Such Tragedy; and Other Myths of 9/11; a Retrospective”. The panel was interesting to me, as I sat at my table, trying to do the math to see if I had made back the $30 I spent to be a part of the small press fair. (See my above note on math class…)

Looking back on the title of the panel now, the writers didn’t discuss the things listed there as straight mythology. The conversation struggled to get past the recollection of the reality of these myths during autumn of 2001, which was remarkable on many levels. The stories that the writers told of their experiences were powerful and interesting. Perhaps the most moving was an anecdote of one panelist’s son’s school that assigned the students to build what should replace the World Trade Towers. One of the kids constructed a building with blocks that featured a hole in the middle of it. “So the planes can go through.” The panelist went on to say how they had felt that irony was dead in the face of the collapsing towers, how poetry then did feel trivial, and how difficult it had been for them to write, for a while.

I timidly raised my hand at one point to raise the idea that as a teenager living in South Jersey, it had been just the opposite. As a shy 17-year-old girl with my future shaping different paths in front of me, still worried about boys and college applications and boys and whether or not I was a good writer… and boys… 9/11 opened a set of doors that led to many different kinds of expression. It gave me, and I am sure many other teenagers, something to write about that adults would actually read, something to say that people would listen to. It gave meaning to my photography. It gave me a prose poem that my Nana still loves to this day, a letter to my high school best friend that he still might have, two products from my high school newspaper that are an important part of history. It gave our output an adult audience, willing to listen and to respond.

But at the panel, I realized everyone my age who didn’t have a direct personal link to the tragedy who had been excited—and scared to death—must have their own small triumphs from the weeks and months following this great tragedy. (I did have a personal connection: a friend of my mother's who I knew from the Philadelphia Folk Festival was a first responder, but I digress--) 9/11 gave us a glimpse into the real world, into the adult world, into a world where our voices mattered, where people listened to us. Things we said and wrote and photographed and joked about, raised money in the streets for, were of consequence. We were in mourning, but we were sarcastic and artistic and moved to action when some adults were afraid to be, when most people felt they weren’t “allowed” to be, when many others were righteously speechless.

***

9/11 is one of those events in human history where everyone who was alive for, born during, or lived in the immediate aftermath of it has a story to tell. Depending on the size of your crowd, swapping these stories can be an experience where you want to jump in as soon as possible to fit yours in or rather one where you wait patiently and listen to the unique factors of everyone else telling theirs. These imprints of that day and its aftermath on our memories push deeper into the tissue of our cerebrums the more we tell them, and they survive in the cultural consciousness the more of them we hear.

I look at television, film, the entertainment that can be found online nowadays, and I see irony abounds. The teenagers that once were the first to reintroduce irony to their small versions of media are now the ones writing articles for The Onion, producing their own art, running their own charities, and laughing at the Daily Show. Irony was never dead, poetry lives on, and the 9/11 tragedy’s imprint survives. As teenagers, we didn’t take the events lightly, but we didn’t let them render us mute, either. We used the day and its aftermath as learning experiences that would help to build us into the stronger versions of the adults we are today.

May the victims of this tragedy be in peace. May those who responded to the tragedy directly be in peace. May the families of the victims be in peace. May they know, though, that the tragedy that took away the lives of people gave others strength, in more ways than one.

Comments

Post a Comment